Filters for Digital Cameras

With film cameras filters have traditionally been used to modify both the spectral content (color) and intensity of light, as well as generating special effects like soft focus. Digital cameras operate somewhat differently with respect to color though. Color modification can easily be done "in camera", and that's what you're doing when you set white balance. So while for film warming and cooling filters, or filters which convert fluorescent light to look like daylight, may be required, digital can achieve the same effects by internal manipulation of the digital data.

![]()

So the first type of filter you really don't need for digital is a color modification filter. These would be warming filters like the Hoya 81 series or the Tiffen 812, cooling filters like the 82 series and fluorescent-daylight conversion filters.

So which filters do you need for digital? Well, there are probably 6 main types:

- A Polarizer

- A UV filter

- A Graduated Neutral Density filter

- A Neutral Density filter

- Filters for Infrared Effects

- Special Effect Filters

1- Polarizing filters

You can't digitally simulate the effect of a polarizer. It can darken blue skies, increase contrast of partly reflecting subjects (like leaves and flowers), and reduce reflections from non metallic surfaces like glass and water. I'd put a polarizing filter #1 on my list of "must have" digital filters and it's my most used filter.

Note that all DSLRs will require a circular polarizer. Digicams generally don't care and are quite happy with linear polarizers. Their effect on the image is exactly the same, but for various technical reasons involving the partly reflecting reflex mirror in DSLRs they need a circular polarizer to avoid possible metering errors (and possible potential problems with AF). Hoya make a line of good circular polarizers. Their multicoated Pro series filters are particularly good, though their regular HMC filters are probably better value. If you want a good filter at low cost, the Tiffen Filters are optically good and quite reasonably priced, though they are not multicoated

2 - UV filters

UV filters block ultraviolet light, which can cause a bluish cast in images shot where there's a lot of UV (e.g. high altitudes). However most people use UV filters to protect the front element of their lens as much as to block UVand they leave it on the lens at all times. I'm not going to take sides in the debate over whether of not it's a good idea to use a UV filter all the time. Certainly using a low quality filter can degrade image quality, but using a good filter shouldn't really have any noticeable adverse effects on the image. I don't personally use a UV filter unless I actually need one.

3 - Graduated Neutral Density Filters

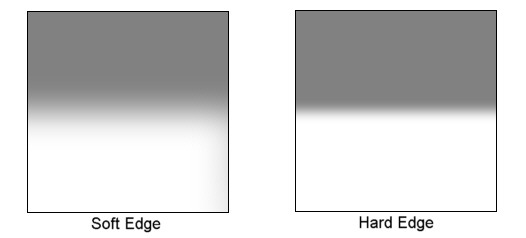

Grad ND filters are used when the dynamic range of a scene exceeds the capabilities of the camera (film or digital) to record detail in both the brightest and darkest part of the scene. The go from clear on one side to a neutral .6D (2 stop) or 0.9D (3 stop) neutral filter on the other. A typical use is to record detail in a bright sky (or mountains) while simultaneously recording detail in a foreground in shadow. You have to hope that the dark/light transition is a straight line though, since that's what a grad ND filter is designed to cope with.

Grad ND filters are available with "soft" and "hard" transitions between the two halves and they are available in a number of sizes with a variety of different holders. The filters are typically much larger than the lens diameter to allow then to be positioned with the transition at any angle and any position in the frame. Typical sizes might be 84mm x 120mm (84mm is the width of a standard Cokin filter holder).

You can also get round grad ND filters which screw into a lens like a normal filter, but unless you always want your dark/light transition running across the exact center of the frame, they may not be ideal.

The above shows the effect of an ND grad. On the left is the "straight" shot. On the right is the effect of an ND grad with the transition across the horizon and the ND part over the upper half of the image.

Note that you can duplicate the effects of ND filters by making multiple exposures and combining them in software. However that means taking multiple images and if you have a moving subject that could lead to problems. For landscape work though (which is where an ND grad is most often used), the digital stitching of multiple images taken with different exposures may be just as effective (even maybe more effective), though it probably requires more effort than just taking the shot using a filter.

4 - Neutral Density Filters

Neutral density filters

simply absorb light of all wavelengths. A 0.6D filter absorbs 2 stops of light and a 0.9D

filter absorbs three stops of light. The major application is to allow the use of slower

shutter speeds or wider apertures than would otherwise possible. For example in bright

sunlight at ISO 100 (the lowest speed on most DSLRs, though some will go to ISO 50 and

others won't go below ISO 200), the shutter speed at f16 (the smallest aperture you should

probably use on an APS-C DSLR to avoid diffraction blurring) is 1/100s.

Neutral density filters

simply absorb light of all wavelengths. A 0.6D filter absorbs 2 stops of light and a 0.9D

filter absorbs three stops of light. The major application is to allow the use of slower

shutter speeds or wider apertures than would otherwise possible. For example in bright

sunlight at ISO 100 (the lowest speed on most DSLRs, though some will go to ISO 50 and

others won't go below ISO 200), the shutter speed at f16 (the smallest aperture you should

probably use on an APS-C DSLR to avoid diffraction blurring) is 1/100s.

If you want a "flowing water" effect when photographing a waterfall, you won't get it at 1/100s. With a 0.9D (3-stop) ND filter you can reduce the shutter speed to 1/12s, which will start to give you that "silky" look for the water. At the other end of the range, if you wanted to shoot at f1.4 in bright sunlight to minimize your depth of field, even at ISO 100 you'd have to use a shutter speed of 1/12500s, which is faster than most DSLRs allow. By adding an ND filter you could drop that to 1/4000s or 1/2000s which most DLSRs do have.

Note that a polarizer will act as about a 2 stop ND filter, so if you have a polarizer, get a 3 or 4 stop ND so you have more options.

5 - InfraRed Filters

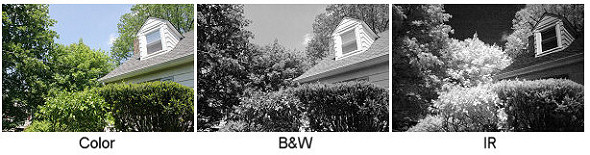

Just about all digital cameras use a filter in front of the sensor which allows visible light to pass but blocks almost all (but not quite all) of the infrared. This is needed because typical sensors are very sensitive to infrared and if it was allowed to reach the sensor it could mess up both exposure and color balance. Since you can't see in IR, you don't need (or want) IR response for general purpose photography.

However if you want the special IR effects (black sky and white foliage) you can use a filter such as the Hoya R72, which blocks all of the visible light while allowing IR to pass though it. Though the camera's IR blocking filter will remove most of this IR light, some will get through, and since the visible light is now blocked, a long exposure will record an image in IR light. In most cases the image will need a long exposure at wide aperture and high ISO settings and so the image will be noisy. There are companies who will remove the IR blocking filters from the camera to enable much better IR response, but this isn't cheap (typically around $500) and will void any warranty on the camera as well as making it tricky to use for normal photography.

6 - Special Effect Filters

The effects of most of these can actually be duplicated digitally. You can do very good soft filter effects for example. Maybe there are a few effects like "starbursts" or multiple images that might be easier to do with a filter than in software, but personally, if I really wanted such effects, I'd probably go the software route since the effects are more controllable.

Which Filters

So assuming you want a polarizer, UV or ND filter, which one should you buy? Actually it's more of which one shouldn't you buy. You shouldn't buy an uncoated filter or a monocoated filter if you can avoid it and you shouldn't buy the cheapest filter you can find since it's important that the glass be flat and the sides be parallel - and that's not something you're likely to find in the cheapest filters. I've been happy with Tiffen filters, though they are sometimes hard to find in multicoated versions.

I've also been happy with Hoya filters. Hoya is probably the major manufacturer of multicoated and supermulticoated filters at reasonable prices. Their filters are very good and their Super Multicoated Pro 1 series have the lowest reflectivity coatings of just about any filter on the market. B+W and Heliopan also make good filters, though they tend to be more expensive then equivalent Hoya filters.

Glass ND grads are available in a number of sizes and from a number of suppliers, for example Singh-Ray (84mm x 120mm) and Tiffen (3"x3" and 3"x 4"). Singh-Ray, Hi-Tech, Lee and Cokin make "optical plastic" filters which are sometimes cheaper and which are more resistant to breakage though they may be more susceptible to scratching than glass filters. The Cokin filters are "graduated grey" and may not be fully neutral. The square or rectangular ND grads attach to lenses using a custom adapter (the Cokin adapters are inexpensive and quite popular).

IR filters are available which transmit different wavelengths of IR. Probably the most useful for DSLR work is the Hoya R72 which blocks just about all visible light but transmits near IR light above 720nm which will (with some attenuation) pass through the camera's IR blocking filter. There are stronger IR filters like the 87C, but these work better with IR film than DSLRs since they only transmit longer wavelength IR which is totally blocked by the digital camera's built in IR blocking filter.