MTF and SQF

By Bob Atkins

Introduction

When it comes to image quality the lens stands as the first,

and possibly most important, link in the chain. Without a sharp lens it’s not

possible to get a sharp image. However to determine if a lens is sharp, and how

sharp it is, we need some sort of objective scientific test method which we can

apply equally to all lenses. The “gold standard” test for many years has been

the determination of MTF or Modulation Transfer Function. This sounds complex

but really it isn’t. It’s simply a measure of how much of the modulation

(contrast) in an object appears in the image of that object as produced by the

lens under test.

Modulation Transfer Function (MTF)

MTF is probably best explained using the image below. At “A”

we see a set of patterns of dark and light bars. There are 4 sets of bars at

increasing small spacings. At “C” we see a line profile of “A”, which is

basically a plot of the intensity across “A” where the white areas have an

intensity of 255 and the black areas have an intensity of 0. (255 is the

maximum intensity of an 8-bit digital image).

At “B” we see what the image of those bars might look like

when they are imaged by a lens. The dark and light regions blur, and the closer

the spacing they more blurred they become. At “D” we see the line profile and

below the plot is the MTF that would be calculated from that data.

MTF is defined as

MTF = (max intensity - min

intensity)/(max intensity + min intensity)

The important point to note here is that the blurring of the

image isn’t necessarily due to any defect in the lens. Even a perfect lens does

this because of diffraction. Diffraction is the tendency for light to spread

out when forced through an aperture. This results in some of the light from the

light areas spreading into the dark areas. When the light and dark areas are

large, this doesn’t have a big effect (the MTF is still quite high), but when

the dark and light areas are small even a small amount of light spread causes a

significant drop in MTF. The result of this is a lowering of the MTF as spatial

frequency increases even for a perfect lens. Of course the degree of blurring

can be worse in the presence of lens aberrations. “Spatial Frequency” is the scientific term used to describe the

spacing of elements in a pattern.

Getting technical

Strictly speaking when we speak of the MTF of a lens, we have to define the type of

test pattern being used. The best pattern from the viewpoint of strict scientific analysis

isn't a step pattern as shown above where the elements are black and white bars. The

preferred pattern is called a sine wave pattern where the optical density varies between

black and white smoothly and the line profile looks like a sine wave. However such

patterns are difficult to make and the image of such patterns is hard to measure by eye,

so most often a bar type pattern is used. Bar patterns actually yield a slightly higher

MTF measurement than sine wave patterns, but the difference is small.

When plotting MTF as a function of the pattern spacing, for a bar pattern the

horizontal axis is in units of line pairs per mm while for a sine wave pattern the

horizontal axis is in units of cycles per mm, but often this distinction is overlooked.

You may see labels such as “lines per mm” or “line pairs/mm”. Note that

lines/mm and line pairs/mm are normally the same thing. In the former case you

count only the black or white lines. In the latter case you count black/white

line pairs.

In addition to the type of test pattern, both the light used to illuminate it and the

type of detector used to record the image also influence MTF. This is because MTF depends

on the wavelength of the light used. Using blue light gives a higher MTF than using red

light for example. Normally white light is used, but even then there would be a difference

between illumination by daylight and illumination by tungsten light. Tungsten light has a

stronger long wavelength component (red light component) than daylight, so MTF measured

under tungsten light would be expected to be lower than MTF measured in daylight. The

detector can matter because if it's more sensitive to blue light than red light it may

yield a higher MTF than if it's more sensitive to red light than blue light.

USAF 1951 Test Pattern

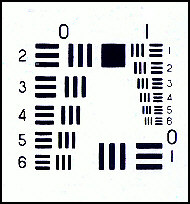

A pattern that has historically been frequently used to make MTF and resolution measurements is the USAF 1951

pattern shown above. It was developed by the US Air Force (in 1951), hence the name!

Above on the right is the pattern itself and on the left is an image of the pattern on film.

By measuring the results on film you can compare lenses, but you can't easily determin lens MTF since

the film will itself limit resolution and lower the system MTF. However you can, with the right

equipment, measure the characteristics of the aerial image formed by the lens and thus directly measure the lens MTF.

Slit Functions and Fourier Transforms

While it’s possible to determine MTF by making measurements

of the images of line patterns such as those shown above there is a faster and

easier way (if you have the necessary equipment). If you look at the image of a very sharp line, typically an

illuminated slit, you can mathematically calculate the MTF of the lens.

Technically what you’re doing is taking the real part of the Fourier Transform of

the Line Spread Function. Sounds complex and it is, but in practice it’s fast

and easy to do, and in fact that’s the way Popular Photography tests lenses.

Below are examples for a good lens (on the right) and a better lens (on the

left). The sharper image of the line produced by the better lens results in a

better (higher) calculated MTF

Here’s a typical MTF plot for a lens showing performance for

both a real and a “perfect” lens. The blue trace (a perfect lens) might

correspond to the “better lens”images

on the leftabove, while the red trace

(a real lens) might correspond to the “good lens”images on the right.

This plot shows MTF decreases as a lens is stopped down and

also that lens aberrations reduce MTF. It also shows why a lens often performs

best around f8, where aberrations are reduced but diffraction is still not

severe.

So what do real lenses look like?

Real lenses rarely, if ever, come close to the theoretical maximum MTF at apertures

below about f8 as stated above, though a few (expensive) lenses may be an exception to

this rule. Performance at the maximum theoretical MTF is called "diffraction

limited" performance, since diffraction is the reason why MTF falls with increasing

spatial frequency, even for a "perfect" lens - thus diffraction ultimately

limits the lens' performance. Below is a plot of the MTF of 6 different 50mm camera lenses

from a study published in 1960. My guess is that current 50mm lenses are not all that

different since 50mm lenses are fairly easy to design and even 40 years ago designs were

pretty good.. The scale of the plot needs some explanation. The horizontal axis reads 0 to

1 and this is the "normalized spatial frequency". What this means is that the

horizontal axis is different for each aperture. The scale expressed in lp/mm would be from

0 to approximately 1800/f, where f is the f-stop. So for the f2 trace, the scale runs from

0 to 900 lp/mm, for f4 it runs from 0 to 450 lp/mm and for f11 it runs from 0 to 164

lp/mm. By using the normalized spatial frequency you can see how the lenses perform

relative to their maximum theoretical performance at each aperture. It's pretty obvious

that none of these lenses comes anywhere close to diffraction limited performance wide

open, and that most of them will show best results when stopped down to the f5.6 to f8

region.

Data from K. Rosenhauer and K.J.

Rosenbruch,

"Die optischen Bildfehler und die Ubertragungsfunktion", Optik

17, 249-277 (1960)

Though we normally think of focusing errors as simply "blurring" the image,

we can look at the effect of defocus on MTF. Below is a plot showing the MTF of a perfect,

diffraction limited, f2.8 lens. Traces are shown for various amounts of defocus (measured

in units of wavelengths of wavefront error). Wavefront error is simply a measure of how

far the image formation is from perfect. Various aberrations, such as spherical

aberration, could also be represented in terms of wavefront error and plots for such

aberrations would appear somewhat similar to the traces shown.

The red region represents an MTF less than zero. In reality what this means is that

black areas appear as white and white areas appear as black, so although a pattern may

appear to be resolved (insofar as you may see black and white areas), in reality it

isn't.Resolution above the point at which the MTF first reaches zero is known as spurious

resolution

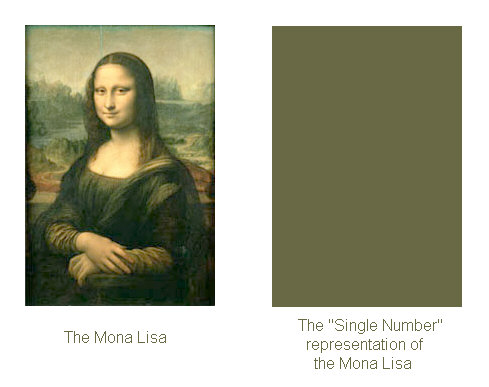

MTF Maps and Single Value "ratings"

We've now defined MTF, but realize that we've only defined MTF at a single point in the

image. The MTF curve at the center will be normally higher then the curve at the edge,

which will itself normally be higher then the curve at the corner. Some authors give an

"MTF" value to a lens which is some sort of weighted average across the whole

image. While this may have some value, it's about the same as describing the Mona Lisa by

it's average color!

Now it's not quite that bad since the MTF "map" will usually be

symmetrical and peak in the center of the frame, but a badly assembled lens may well show

asymmetric behavior that a single number misses and even if the lens is symmetric a single

number doesn't tell you how MTF varies across the frame. A lens with high center MTF and

low edge MTF may have the same "average" MTF as a lens that has a medium MTF

value all across the frame.

MTF is a very powerful measure of lens performance. It can be used, for

example, to calculate the effects of defocus or other aberrations on the image.

However plots such as the ones above are for a single point in the image. Each

point will have its own MTF curve! There’s an alternative way to plot MTF data

and that’s to plot MTF at a given spatial frequency as a function of the

distance from the center of the image. Such a plot is shown below. The data

is for a Canon EF20-35/2.8L lens at 20mm.

Blue lines are for f8, black lines for f2.8

Solid lines are radial measurements, dashed lines are

tangential measurements

Thick lines are for 10 lines/mm, thin lines are for 30

lines/mm

Image taken from

“Lens Work” published by Canon.

As you can see, things get quite complicated quite quickly –

and this plot only shows data for two apertures at two spatial frequencies and

two target orientations (radial and tangential lines). MTF varies significantly

across the frame and the lens shows significant astigmatism (difference between

radial and tangential MTF). Radial lines

are those that point towards the center of the frame, Tangential lines are those at right angles to radial lines. If

you think of a spoked wheel with the hub in the center of the frame, the spokes

would correspond to radial lines, while the rim of the wheel would be made up

of tangential lines.

Now take the above plot and try to assign a single number to describe it!

One problem with using MTF plots to judge image quality is

that it’s very difficult for the average user to correlate MTF plots with image

quality. MTF is a purely objective measurement and is ideal for the exact

scientific measurement of the optical performance of a lens but it doesn’t take

into account any aspects of human vision – which after all is what we use to

look at an image – and that’s where SQF comes in.

Subjective Quality Factor

SQF was developed by Grainger et al in the 1970s [1] to

provide a more easily understandable measure of image quality which takes into

account not only the intrinsic quality of a lens, but also the nature of how we

see things.

It has been demonstrated by experiment that human vision has

a bandpass characteristic whereby we see some spatial frequencies better than

others. Just like a lens, the higher the spatial frequency of the detail we are

looking at, the more difficult it is to resolve. However unlike a lens, the

human visual system also doesn’t see very low spatial frequencies well. The

high frequency falloff is probably due to the optical limitations of the eye’s

lens, but the low frequency falloff is due to the physiology of the retina and

the way the brain interprets visual information. So the human visual system can

be considered to have an “MTF” which peaks as shown below:

As you can see there is a peak at 6 cycles per degree. This

translates to 1 cycle per mm for a print that is viewed at a distance of 34cm

(about 13.5”). What this means is that when you view a print from that

distance, which would be typical for close viewing, the MTF at around 1

cycle/mm in the print would have the most influence on whether you thought the

print was sharp or not. Grainger found that he could correlate the subjective

impression of sharpness with the MTF of the spatial frequencies in the print

that correspond to the human visual response between 3 and 12 cycles per degree

which turns out to befrom 0.5 to 2

cycles per mm in the print when viewed at a distance of 34cm.

Grainger then developed a model, which basically states that

the subjective sharpness of a print corresponds to the area under the MTF curve

between the spatial frequencies of (0.5 x magnification) and (2 x

magnification) when spatial frequency is plotted on a logarithmic scale. He

verified this model by making prints using optical system with known MTFs and

asking viewers to rate the images in terms of sharpness and he found very good

agreement between his calculated SQF values and the subjective rating of image

quality by viewers.

So to give a concrete example, if we make an 8x10 (or 8x12)

print from a 35mm negative we have to magnify the negative by a factor of 8

(since the negative is approximately 1” x 1.5”). So as far as the SQF is concerned,

the area under the MTF curve of the lens between 4 and 16 cycles/mm is then

what really counts. The higher the MTF is in that region, the higher the print

quality will appear to be and the higher the SQF will be.

This figure shows how MTF and SQF are related. The MTF is

plotted for a “perfect” f2.8 lens (diffraction limited, no aberrations), a real

f2.8 lens operating wide open (blue trace) and that same lens stopped down to

f8 (brown trace). At f8 this lens isn’t quite perfect (it’s not diffraction

limited), but residual aberrations are very small. For a 4x enlargement to a

3.5 x 5 print the SQF is related to the area under the MTF curve as shown on

the left. As you can see, the area under the blue curve is very slightly greater than that under the

brown curve, though lenses would probably produce an equally good print. That’s

reflected in most lens tests where almost all lenses get an A+ rating for 3.5 x

5 prints.

The area on the right represents a 10x enlargement to a 10 x

15 print. This time you can see two things. First the shaded area is smaller

than that for the 4x print, resulting in a lower SQF. A 10x print won’t look as

good as a 4x print. Second you can see that now the lens at f8 has a slight

advantage. Prints made with the lens stopped down to f8 will appear sharper.

This data also shows something you might not expect, that,

on the basis of SQF, it’s possible for lens “A” to be better than lens “B” for

small prints, but lens “B” may be better than lens “A” for large prints.

Normally this doesn’t happen, but it is possible. It also follows from this

that it’s possible that prints from

lens “A” may look better than prints from lens “B” when viewed from a distance,

but when viewed closely prints from lens “B” may look better than prints from

lens “A”! This would be an unusual situation, but it could happen.

Interestingly, in the 1980s a Swedish research group showed

that subjective image quality could even be predicted from a simpler method

that looked only at the MTF at a single spatial frequency rather than over a

range of spatial frequencies as Grainger’s model does [2]. However Grainger’s

model probably applies to a wider range of lenses with a wider range of

aberrations and so may give a more accurate prediction.

While we can state SQF to any degree of precision (e.g. 95,

95.1, 95.123 etc.), Grainger found that it really takes about 5 points

difference before most viewers notice a difference in image quality. So while

most viewers would not notice a difference between images with SQFs of, say, 88 and

90, most would notice a difference between, say, 88 and 93. This is indicated

in the Popular Photography lens tests by the different color shading of the SQF

values and the A+, A, B+, B etc. ratings which are spaced by 5 SQF units, as shown in the example below.

Since SQF is derived from MTF and as we saw earlier every

point in an image has its own MTF characteristic, so every point in an image

has its own SQF properties. In order for SQF to be useful it needs to address

the whole image. To do this, the Popular Photography test splits the image into

three regions. The center of the image accounts for 50% of the final SQF. 30%

of the final SQF is determined by the SQF at a point 50% way between the center

and the corner and 20% of the final SQF is determined by a region 80% of the

way to the corner. At each point radial and tangential measurements are

averaged.

For example suppose we calculate an SQF of 90 in the center,

81 50% of the way to the corner and 60 80% of the way to the corner. The

combined SQF would be (90 x 0.5) + (80 x 0.3) + (60 x 0.2) = 81, and that’s the number you’d see in the

lens test - 84

Of course you'd also get an SQF score of 81 if the SQF were 81 at all points in the image (81 x 0.5) + (81 x 0.3) + (81 x 0.2) = 81. You still get an 81 with an SQF of 100 at the center, 90 at 50% of the way to the corner and only 5 at 80% of the way to the corner (100 x 0.5) + (90 x 0.3) + (5 x 0.2) = 81. This again shows up

the problems of a one number measurement. It doesn't tell you how the image quality is distibuted across the

frame.

Whether MTF of SQF is a more useful measure of lens quality depends on who is reading the results. MTF curves are

more complex and more difficult to interpret, but they contain more information. The problem is that if you don't

understand them, either they are meaningless to you or may even mislead you if you don't know that you don't

understand them! SQF on the other hand was designed to

be a simple system which anyone can understand. It reduces image quality to a single number again, so it's not (nor is it intended to be) a technical measure of optical quality. It's a number which a typical consumer can use to get some idea of the relative overall quality of images shot with different lenses at different apertures and printed at different sizes. Though it's an objective measurement, it's based on human visual response as well as the intrinic quality of the image formed by the lens, and so may preduct a subjective response to image quality.

As single number SQF value is probably more useful than a single number MTF value because it at least factors on the characteristics of human vision. However a detailed MTF plot contains much more information, which will enable a skillful and educated reader to better evaluate a lens.

References

[1]”An optical merit

function (SQF) which correlates with subjective image judgments”,

E.M.Grainger and K.N.Cupery, Photographic Science and Engineering, Vol 16, #3,

pp221-230 (1972)

[2] “Lens performance

assessment by image quality criteria”, K. Biedermann and Y. Feng, Image Quality: An Overview, Proc. SPIE

Vol. 549, pp36-43 (1 985)

© Copyright Bob Atkins All Rights Reserved

|