Photographing Comet Panstarrs

Comet PANSTARRS on March 3rd 2013, in the constellation Sculptor.

Photo taken from Las Campanas observatory, Chile. Photo courtesy Yuri Beletsky via Wikipedia

Around this evening (March 7th 2013) comet PANSTARRS (also known as C/2011 L4 ) should start becoming visible in the evening skies. While comets are usually named after the person or persons who first observed them, in this case it's named after the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS), an automatic sky survey telescope system on the summit of Haleakala on Maui, Hawaii. For observers in the nothern hemisphere it will appear out the the glare of the sun around the March 7th and then slowly move further north and west (and away from the sun) during the rest of the month. Despite early predictions that PANSTARRS could be a very bright comment, the currentpredictions are that it should only reach 2nd or 3rd magnitude which isn't spectacularly bright, especially in the twilight skies after sunset, but it should still be visible to the naked eye and should be quite clear in binoculars.

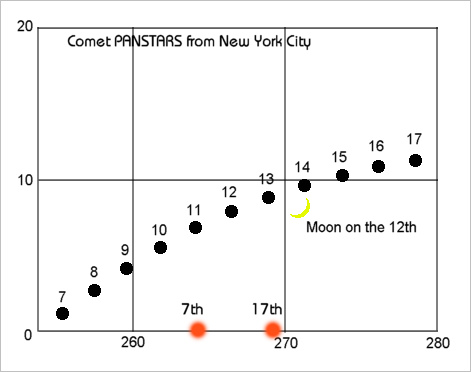

The chart below gives the approximate position of Comet PANSTARRS about 30 minutes after sunset between March 7th and March 17th from mid-latitudes (around 40 degrees north). It's approximately correct for most northern latitudes give or take a few degrees. This should be the period of maximum brightness. Perihelion (closest approach to the sun) is on March 10th and the comet should be brightest then.

The tail of the comet, if visible, will point away from the sun.

Position about 30 minutes after sunset from mid-northern latitudes in March 2013

The red stars show the approximate position of sunset on the 7th and 17th of March 2013

The chart also shows the position of the crescent moon on March 12th when the comet will be about 5 degrees (10 moon diameters) to the left of the moon. As the days pass the moon will get brighter each evening, which isn't going to help comet visibility if it is faint.

Photographing PANSTARRS

How difficult it will be to photograph PANSTARRS and which lens to use will depend somewhat on how bright it gets and what type of tail it develops. As I write this (March 7th 2013) the last report from the southern hemisphere was that the comet was at around magnitude 2 before it was lost in the glare of the sun.

The first requirement for photography is a clear horizon to the west. The comet will be low in the sky. It won't get much more than about 10 degrees above the horizon while it's at its brightest. That's just 20 moon diameters. So if there are buildings, trees or mountains to your west, they will block your view.

The second important point is that this will be twilight photography not night photography. The sky will still be relatively bright astronomically speaking. The sky doesn't get really dark until the sun is around 18 degrees below the horizon and by that time the comet will also be below the horizon! The upshot of this is that you won't be able to use very long exposures because the sky will be too bright.

If you want the comet - and any stars in the shot - to be as sharp as possible when shooting from a stationary tripod, the shutter speed must be chosen on the basis of the table below:

Focal Length |

Critically Sharp. > 1 pixel movement |

"Sharp enough" for small prints? |

| 1000mm | 1/20s | 0.5s |

| 500mm | 1/10s | 1s |

| 300mm | 1/4s | 2s |

| 200mm | 1/3s | 3s |

| 100mm | 1/2s | 5s |

| 85mm | 0.7s | 7s |

| 50mm | 1s | 10s |

| 35mm | 1.3s | 13s |

| 28mm | 1.7s | 17s |

| 24mm | 2s | 20s |

These shutter speeds will "freeze" the motion of the stars and comet due to the earth's rotation. There's also another limit on shutter speed and that's the time it takes to expose the sky and not "blow out" the image. You really don't want the sky much brighter than a mid-grey (or blue) tone or the comet won't stand out. This is something you'll have to determine by experiment. Just look at the histogram of your image on your camera's LCD screen. You don't want the center of the "hump" past the center of the histogram range.

Since the exposures you'll be using will record foreground details, for artistic effect it would be nice to have an interesting foreground. Perhaps a lake reflecting the sky or a beach and the ocean. However you take what you can get. A clear view to the western horizon is your primary requirement. After that you can look for something aesthetic!

The moon will be closest to the comet on the 12th, but getting both of them in one shot with one exposure won't be easy. The moon will be much, much brighter than the comet, so an exposure for the moon probably won't show the comet and an exposure for the comet will totally overexpose the moon. If you don't object to photoshop trickery, splicing together two images is probably the best way to go, though you'll have to work to get the sky density the same in the two images.

So good luck if you try to photograph comet PANSTARRS. This will be your only chance. If it does ever come back it will be around 100,000 years from now. If you miss this comet there's another one on the way. Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON) will be here in the fall and visible (from the northern hemisphere) in the evening sky through October and November, passing by the sun in late November and reappearing in the morning sky. It could well be the brightest comet in the last 100 years, but comet watchers know that comet brightness is very, very difficult to predict and it's entirely possible it will fizzle out and be nothing special. Keep your fingers crossed that it lives up to the predictions.

UPDATE March 14th

I finally managed to see an get a couple of shots of the comet. I tried first on March 9th from a very good location but saw nothing. The next clear night was March 14th. This time the location wasn't so good but with the comet being a little higher and setting longer after the sun in darker skies I manages to spot it. It wasn't a naked eye object, but it was just visible in binoculars. I pointed my 300/4L lens in generally the right direction and hoped for the best. This is what I got:

Comet Panstarrs from NJ. 8pm on March 14th. 0.6s at f4.0, ISO 6400, EOS 7D + EF300/4L USM

No more clear skies at sunset are forecast for the next 10 days here, so I won't be posting any more images for a while :-(

UPDATE 2 March 19th

A very brief gap in the clouds this evening at sunset allowed a second glimpse of the comet. Again not a naked eye object from here in New Jersey.

PANSTARRS - March 19th. Canon EOS 7D + EF 300/4L USM, ISO 3200, 2s @ f4

UPDATE: April 2nd 2013

The comet is definitely fading and isn't a naked eye object during the time it's above my horizon, but it's just possible to glimpse in binoculars and still fairly easy to photograph - once you figure out where to point the camera!

The above image is a composite of 16 images, each 1s at f4 and ISO 6400 on an EOS 7D using an EF 300/4L lens. The images were stacked using DeepSkyStacker.

For more astrophotography information see:

- Fixed mount Astrophotography with a camera and lens

- Photography of the Sun, Moon, Planets and Stars

- Photography of Comets and Constellations